Housing First is a phrase I hear a lot in my line of work. As defined by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, Housing First “is a recovery-oriented approach to ending homelessness that centers on quickly moving people experiencing homelessness into independent and permanent housing and then providing additional support and services as needed.”

I believe that in a first-world country like Canada, housing should be a reasonable human right. So, in that spirit, I attended the UNB Housing Summit on Nov. 22, 2022 at the Nick Nicolle Centre in Saint John.

UNB professor Dr. Julia Woodhall-Melnik began by ephasizing affordable housing is always linked to adequate and suitable housing. Woodhall-Melnik, who is an associate professor of social science at UNB, the principal investigator of the Housing, Mobilization & Engagement Research Lab (HOME-RL), and the new Canada Research Chair in Resilient Communities, said we can not understand one component without understanding the other two.

During the summit, various speakers offered examples of how housing issues are dealt with in other locations. In Hamburg, Germany, for example, municipalities sign multi-year contracts with developers following the rule of thirds when they plan buildings with more than 30 units:

- 1/3 regulated rental

- 1/3 market ownership

- 1/3 non-profit

“All levels of government must acquire homes at risk of becoming unaffordable and also purchase land and non-residential buildings to convert to affordable housing, said Carolyn Whitzman of the University of British Columbia.”

Whitzman is an advocate ot the Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) strategy, which states that municipalities should provide permanent housing–not shelters–with appropriate mental-health support, to low-income people at risk of homelessness. She gave the example of St. Thomas, Ontario, where the homeless population is 0, to emphasize that the HART goal is possible in Canada.

The NB Housing study–conducted by HOME-RL at UNB-SJ– addressed mental health issues and housing. Those surveyed for the study were on the NB Housing wait list. The study found that 34 percent had a serious mental illness, 60 percent had slight-to-extreme difficulty walking, and 82 percent experienced slight-to-severe pain/discomfort.

In this study mentioned above, it’s relevant to emphasize that 65 percent of those surveyed were not seniors. Forty percent completed high school, and 69 percent are unemployed. These findings need to be taken seriously by decision makers and we all need to reflect the connection between people’s mental health and housing struggles. And these struggles are exacerbated by the fact that housing applicants may wait more than a year for adequate housing.

“The hourly wage required to provide the basic necessities of life in Saint John should be 21.60 CAD an hour, otherwise, there is no way to pay rent, groceries, utilities, transportation, etc,”’ said University of Alberta professor Damian Collins. The current provincial minimum wage is 13.75 CAD.

Collins presented a study stating that by 2007, Canada’s homelessness crisis had become the worst since the great depression.

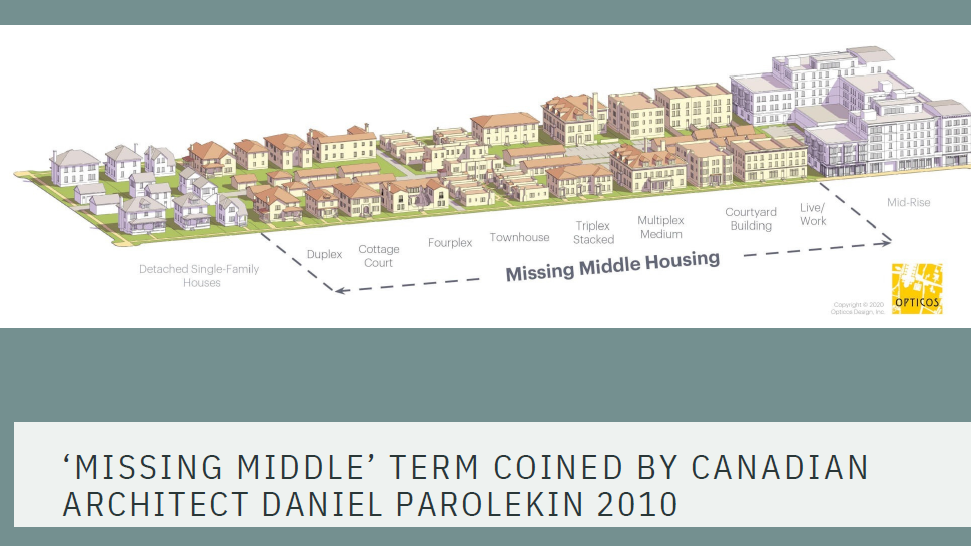

Instead of one solution, Professor Damian suggested 20 five-percent solutions, the first of which is to unlock new housing supplies within cities. Most land in Canadian cities is zoned for low-density residential uses. In Canada, we are missing something in between single houses and huge condos.

Secondary suites can be basements and garage suites. This strategy allows us to use the units that are already in place, reducing costs, increasing density in existing neighborhoods and supporting multigenerational living.

This picture provided by Professor Collins shows a garage converted into a two-floor unit in Edmonton.

Homelessness: Easy to enter, hard to exit

Homeless camps are now a permanent feature in some cities of Canada, Collins said. The housing market makes homelessness “easy to enter, hard to exit,” he said. ”We need a commitment to regulating housing prices.”

Saint John has an official homeless count of 165 people, though local non-profit organizations report higher numbers.

“You can take people out of homelessness, but if you’re not stopping new people from falling in, it’s a cycle that will never end,” said Collins.

Three more encouraging solutions are: mixed use housing, affordable housing and an increase in the minimum wage.

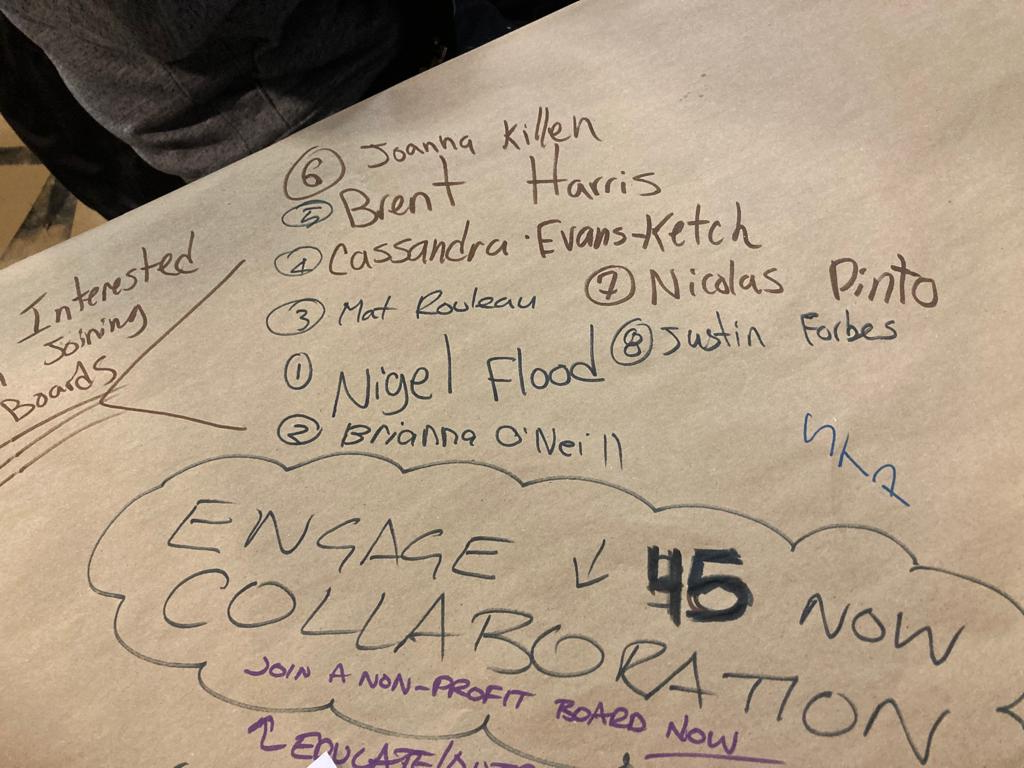

During the housing summit, we had different round tables and table discussions. In my table, what we enforced was to bring new leaders into the housing topic and we got a list of 8 committed people. It was a good exercise. Besides that, we all agreed to have more housing summits like this one.

The highlight of the summit was meeting Professor Julia Woodhall and her team, and renewing our efforts to collaboratively change this region with Housing First.